You could’ve easily missed the signs that Spanish Flu was coming back for a second wave at the end of summer in 1918. In mid-August, New York City had suffered a scare when a Norwegian steamship arrived in port with many suspected cases. Even before the city’s health department confirmed any cases of Spanish Flu among the sick, panic began to rise and the department warily advised people not to kiss “except through a handkerchief.”

That news did push its way onto the front page of many Boston-area newspapers, but below the fold. The country’s attention was firmly fixed on war news from the front in Europe, a new bill in Congress on the military draft, and the coming World Series–the last the Red Sox would win until 2004. No one expected the Spanish Flu from the past Spring to roar back to life and become history’s worst pandemic.

What was the Spanish Flu pandemic like in Massachusetts? How did it change everyday life more than a century ago? Read on to find out six quick facts about the Spanish Flu in Boston and in Massachusetts.

Fact #1: The Spanish Flu Re-Emerged in Boston

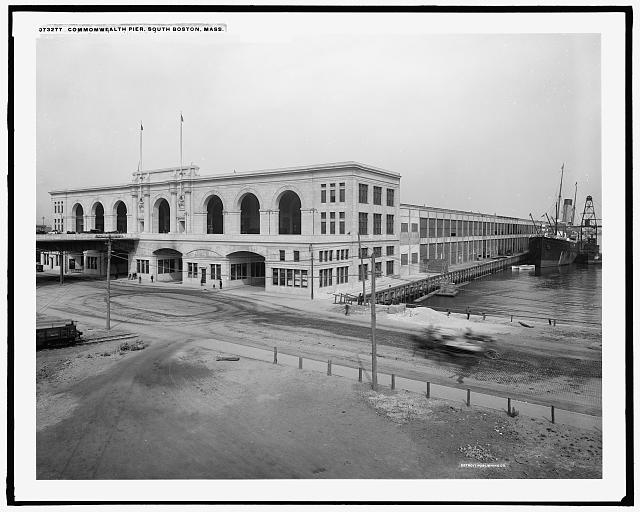

A soft breeze was blowing out of the northwest when two sailors stationed at Boston’s Commonwealth Pier came into sickbay complaining that they weren’t feeling well. The next day, eight more followed, and then 14 more by the end of the week.

Even the most vigilant flu watchers might have let their guard down on those warm days at the end of that summer in 1918. They didn’t yet know that the second wave of Spanish Flu had reemerged in Boston, months after the pandemic’s first wave of infections had subsided.

Military officials tried to contain the outbreak, moving seemingly healthy soldiers to Framingham and canceling a train of sailors bound for Charleston Naval Yard in South Carolina. It was too late. By mid-September, nearly one of every ten sailors (some 2,000 men) in the Boston area was sick with flu. Forty miles inland, at the Camp Devens Army installation, flu had already started spreading among its 50,000 men.

In the following weeks, new cases emerged among civilians in Boston, Brockton, Quincy, Gloucester, and across Massachusetts. A few weeks later on October 1, Massachusetts was reporting 85,000 cases with 200 deaths a day in Boston alone.

The second–and worst–wave of the Spanish Flu pandemic had begun.

Fact #2: Fake News Existed Before Social Media

As influenza cases and death tolls mounted in Boston and statewide, panic fueled misinformation and fear. What were the symptoms of the flu? How could it be distinguished from the common cold? What could keep people safe and save lives?

Reports emerged that drinking lemon juice or eating raw onions could beat back the flu. The Committee of the American Public Health Association (A.P.H.A) lobbied for laws that would have outlawed sneezing or coughing in public.

Meanwhile, the American public grasped for any means to protect themselves from infection. Stories emerged of people avoiding tight shoes and clothing, pushing salt up their noses, or boiling red peppers after closing all the windows in their home.

Fact #3: Schools Were a Flashpoint Issue

Boston officials initially claimed that children were safer from the flu at school, where they could be monitored by physicians and nurses. They argued that a few cases would likely appear, but that schools should remain open.

“The conditions won’t improve through worry,” William C. Woodward, Boston’s Health Commissioner, said on September 18, “they are likely to become worse.”

Parents began to keep their children home anyway. Other districts in Massachusetts closed. In Boston, schools stayed open for the city’s 110,000 schoolchildren. Officials kept reassuring parents that their children were safe–until an eight-year-old student died, and then a 17-year-old student died next.

Those deaths got the attention of Governor Samuel McCall. Before an official order could be issued, though, the Superintendent finally closed Boston schools on September 25.

Fact #4: People Sought Open Air for Safety

Like today, people felt safer outdoors during the Spanish Flu pandemic. Health officials set up open-air emergency camps in many Massachusetts cities and towns to treat the infected. The first opened on Brookline’s Corey Hill on September 9. Gloucester, Ipswich, Brockton, Waltham, Haverhill, Springfield, and Barre soon followed.

The city of Lawrence opened its own emergency camp for flu victims from the city, as well as for cases from the neighboring communities of Methuen, Andover, and North Andover. Controversy surrounded the opening of the Lawrence camp, named Emery Hill, which had been a large dairy farm that supplied milk to nearby residents.

Despite the residents’ loud objections, however, city officials insisted that the state had chosen the site and that there was little they could do. By October 12, the camp had 150 patients.

Fact #5: They Still Fought about Masks

Authorities advised that wearing masks helped prevent the spread of flu. People who resisted were called slackers, the same term used to describe people who did not help the ongoing US war effort in World War I. In western cities like Phoenix and Denver, officials issued mask orders.

People generally complied with the orders, as they were seen as a way to keep troops healthy and help with the war effort. Still, masks, then as now, had their detractors. In San Francisco, a band of citizens formed the Anti-Mask League. Police in Buffalo, New York were required to wear masks, but could cut holes in them so they could smoke.

Much of the support for masks during the Spanish Flu pandemic drew on the support for the troops fighting in the world war. When the war ended that November, support for masks began to wane.

Fact #6: The Pandemic Ended, Just Like This One Will

By the end of the pandemic in 1920, about one-third of the world’s population, some 500 million people, caught Spanish Flu. Over 50 million people died, with 675,000 of those deaths in the United States.

In the US, more than one in every four people suffered some form of the Spanish Flu, and within one year of the outbreak, the average life expectancy for a US citizen was shortened by 12 years. Even today, it remains the deadliest pandemic in human history.

This piece was originally published on Forgotten New England in December 2011, and has been updated in October 2020.

Your entries never fail to be fascinating, Ryan. I had no Idea until now that there were tents like this.

The influenza epidemic actually was a large reason why WWI ended.

In the school year of 1917-1918 my grandmother was a nursing student at the Waltham Training School For Nurses. Before she died, my aunt Anna told me that my great grandfather pulled my grandmother out of nursing school out of fear she would get sick and die. Your article here has greatly sharpened the focus on this timeline for my family history project, especially the mention that tents were set up in Waltham. I suspect now that the nursing school was probably involved in caring for victims in Waltham and would be greatful if anyone could confirm this.

Hi David, you’ve suspected correctly. According to a volume of Nursing World dating from 1918, “During the Spanish Influenza epidemic in Waltham, the Waltham Training School for Nurses has served as headquarters for all the activities aimed to combat the disease, the authorities at the city hall having at an early stage turned matters wholly over to the school.” The issue of Nursing World containing this excerpt and more information can be found here. Hope this helps! Best of luck with the project.

Thank you for sharing information about the 1918 influenza epidemic.

My grandfather owned Chenette’s Pharmacy in Indian Orchard, MA from 1904 to 1918. He was a pharmacist himself when he died of influenza leaving behind my grandmother and my father, who was 5 years old.

I’ve been trying to find out more information about this.

Hello

Both my great grandparents died on Nov 11, 1918 and they were residents of Indian Orchard, They left my grandmother and younger siblings. My 19 year old grandmother became head of the house. I did not think she ever over came the trauma.

I just began my genealogy search on my husband’s side of the family. He and his mom told me that my husband’s great grand mother had died in the Spanish Flu epidemic. Upon further research, I was able to deduce that she did indeed pass away in 1918 but I’ve been unable to locate much else in way of validation (grave marker, death certificate). Looking at your blog shows how scarce things were at that time and the record keeping for the vast amount of victims during that time would have been difficult to maintain. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and bringing light to a horrible event in world history.

Does anyone know if there exists a list of names for people who died during the Flu epidemic of 1918. My 3rd great grandparents on my mothers side both died during 1918, but I don’t have exact dates

There is no list as such. However there are many sources of the information you seek. If you know the town they died in that is the best start. Also, many genealogy websites have databases that may include the information you seek. If you know the town they died in then go to the town hall and ask them to look for a death certificate. If they can’t help you or want to charge you a fee, go to the main branch of the public library in that town. Then ask to view town reports. Most towns will include all deaths that occurred in the town that year and will give a date. Another way is to look up on the internet the time period when the Spanish flu affected the area your third great grandparents died in then look at obituaries in the local paper. Obituaries will give you either exact date or a very close approximation. Grave stones usually have death dates written on them. If you know where they are buried you should find the dates there.

My grandparents grew up in Lawrence, and were 15 at the time of the epidemic. Maybe they knew your grandfather! My grandmother was the only one in her family of 8 who did not get it. She was told to stay outside in “fresh” air as much as possible when not caring for her family members. From her perch, she would see the wagons go past with the bodies of their neighbors. As far as I know, none of her or my granddad’s family died. Recent research suggests that what didn’t kill didn’t make you stronger, however. Now they’re saying that that flu strain weakened victims’ hearts and immune systems.

Hello! Great blog! I’m looking for photos of the tent camp that was set up for the flu patients in Waltham. I believe it was called Camp Jensen. Do you know of any resources? Thank you!

Hi Rachel. My grandmother was a student at the Waltham Training School for Nurses. She was also an amateur photographer. I have such photos in my storage unit though at the moment I am unable to travel to that city to retrieve them. They are safe and I hope one day soon to retrieve them and scan them and post them here. They are unpublished and show the tents with the patients my grandmother was caring for.

Hi David,

I’d also be very interested in seeing your grandmother’s photos of Camp Jensen in Waltham. A recent Waltham Historical Society talk on the 1918 flu epidemic discussed the nurses and their heroic work at the tent camp. The camp was apparently built on the Paine Estate.

My grand-father was born around 1896. I remember hearing he was married and his wife died a short time later before he met and married my grand-mother. I’m betting she died from the Spanish Flue

Anyone have any information about sports and recreation activities being cancelled in New England during the 1918 pandemic? I know there are reports of schools being closed. I’m looking for stories of how students were dealing with sports and recreation being cancelled, suspended, and postponed. Thanks!

My great grandparents lost 2 children and 2 grandchildren from the flu within a few months of each other in 1918. They lived in Lowell, MA.