Genealogists spend a lot of time immersed in old records – especially really old ones, from decades and centuries past. These records yield valuable information in building family trees. And, as any genealogist will tell you, every tree ends at its treetop, with the names of its brick wall ancestors, those whose parentage is unknown and likely unrecoverable from surviving paper records. But, even paper records have their limits. Beyond providing names of relatives, birth-marriage-death dates, and possibly military service details, very little is recorded about the person.

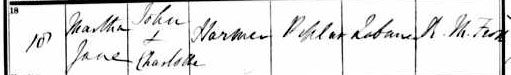

Sure, if I look at the surviving paper records for Martha Jane Harmer, my wife’s second-great-grandmother, I’ll learn that she was born in Bow, a London suburb, in 1858. Her baptismal records reveal her parents’ names (John and Charlotte) and that she was baptized in the Anglican church. UK census records show that she lived in the area until the early 1880’s when she married and moved to the United States.

But, that’s pretty much where the trail runs cold. Sure, you can extend the treetops of your family tree by learning the names, locations, and vital dates of Martha’s ancestors, but, in the end, you’ll have a list of names. These provide some interesting insights into the naming patterns of earlier times and surnames (and their histories) in your family background, but family historians wonder what their ancestors looked like (which physical traits have been passed down the generations), what their ancestors did (which talents come from earlier generations), and how their ancestors behaved and interacted with each other, and the larger world (what maddening vexations have been passed down the generations).

Studying genealogy for years, it’s so tantalizingly irresistible to blast photographs of ancestors with your brick wall questions – ‘where were you born?’ ‘who were your parents?’ ‘what was your mother’s maiden name?’, or ‘what did you see growing up?’ Any of those answers, recorded anywhere, would be invaluable.

It’s every family historian’s dream. You come across an old box of photographs. Inside, there might be a photograph of an ancestor, maybe even labelled. My in-laws, descendants of Martha Jane Harmer, had just such a box. And, with their family being much more cognizant of posterity than mine, someone actually took the time to label the photographs. This is genealogical gold.

With that, Martha Jane Harmer, a young Martha Jane at that, has a face. But, there was more. Deeper in the box, there was a yellowed envelope, its paper made fragile by age. Inside, there’s ancient paper, folded into thirds, lined, with light, uneven handwriting looped and swirled across its surface. A careful unfolding reveals that it’s a letter – to the future – telling posterity about Martha Jane’s memories from her childhood in Poplar. If only all ancestors in my tree were so informative to the future genealogist.

The letter, some five or six pages long, provides a view, deep into the 19th century, of Martha Jane Harmer, her life, and the lives of her family. As I read through the memories of a woman whose passed away in 1934, I learned about her grandfather, Charles Harmer, who arose every Monday morning, readied his horse, and then drove through the English town of Acton to collect rents from his tenants. I read about John Harmer, his son and Martha Jane’s father, who collected the money, running from door-to-door as Charles rode the carriage along the road. I also learned that, one day, young John jumped from the carriage, twisting and breaking his leg on the curb. So bad was the break, the story went, that even after the doctor set it, the leg healed shorter than the other. For the rest of his life, John Harmer wore shoes specially made with an elevated sole.

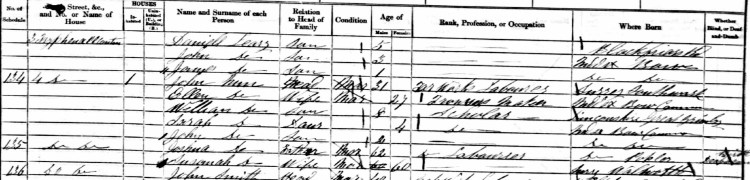

The letter next recalls Martha Jane’s maternal grandfather, Joshua Nunn, who saw his Harmer grandchildren often. It also reveals that Joshua was deaf and dumb from birth. An old Nunn family story told of how Joshua Nunn’s mother, when she was young, had wished for children who were deaf and dumb. Family lore had it that she got her wish – twice over, Joshua and his brother could not speak or hear. As I read through the letter, I thought this was just too fantastical, but the 1861 UK census proved otherwise:

Some of the letter’s charms cannot be verified in surviving records. They go beyond what was recorded, and would have been lost forever if they hadn’t been captured in those handwritten pages so long ago. One tale records that Martha Jane’s mother, Charlotte, would put two raw eggs in egg cups for Grandpa Nunn each time when he came to visit them. He would smile, get the eggs and suck them. Martha Jane’s father, John, could be a prankster and, one day, put up two eggs that had been emptied. Even though everyone thought it was a good joke, Grandpa Nunn looked so disappointed that Charlotte soon brought in two eggs to take the place of the empty ones. Martha Jane also recalled how she and her two older sisters, Emma and Betsy, would pass their Grandma Harmer’s home each day on the way to school. Grandma Harmer would invite them in for sardine sandwiches and make sure they used the outhouse before continuing on for home.

Martha Jane recalled the bad times too. She remembered how, on Good Friday in 1866, her mother died, one day after setting up sponge for hot cross buns. She was just 32 years old. One day earlier, on Holy Thursday, she had the girls bring in the bread board to the bedroom. She made the buns ready for the oven and then passed away the next day. In the letter, Martha Jane recalled how, as the end came, Grandpa Nunn stood looking at his daughter. He then said the only words that he had ever spoken in his life. “Poor Charlotte.” He died the following week.

The letter also records other memories from Martha Jane’s childhood. When she was about three years old, she was playing at a curb by the alley with her sisters. A man in a horse and wagon came along and the horse stepped on her jaw. The neighbors thought she was killed and carried her into her mother. The doctor was called. In the end, although she recovered, when she would be busy sometimes, you could see that she held her mouth out of line.

After Charlotte’s funeral, John Harmer tried to keep the children and the home together. Different relatives came to keep house. Some took the nice sheets, pillowcases, and anything else they wanted. John had a hard time taking care of their youngest daughter, Louise, who was just two years old. He also had a hard time taking care of himself. The letter recalls that he ‘just lost heart’ and died the year following his wife’s death. When John died, the girls were still young, between nine and thirteen years old. Louise was just three, and went to live with relatives.

The letter continues from there, for several more pages, recalling Martha Jane’s years after her parents’ deaths. She and her older sisters found work in town as servants. Martha Jane worked in several homes and lived with a series of relatives, some of whom she recalled fondly, some not so much. For a while, she lived with her cousin Mary Ann’s family. Mary Ann is remembered as a ‘husky girl’, who would wake Martha Jane up at night to hold the candle while they went downstairs into the room where the family’s milk was cooling in a large stone jar. Mary Ann would skim a cup of cream off the surface and drink it. It wasn’t until years later when Mary Ann got married that Martha Jane’s Aunt Mary admitted to her that she knew it was her own daughter stealing the cream, and not Martha Jane. Aunt Mary is also fondly memorialized as a woman whose temper grew so frightening that one day, she broke a large mixing bowl over Martha Jane’s head, which left Martha Jane in considerable pain for several days.

Martha Jane’s Aunt Mary is a formidable character, but at her house is where she met her future husband, James Williams. He’s remembered as a young carpenter who boarded at Aunt Mary’s for a few years while he was building homes in London. One day after completing a lot of the work, James went to the owner to draw some pay – only to learn that his construction partner had already drawn the pay for both of them, and spent it. James confronted the other man, and left him to finish the work. James departed for America soon after, promising Martha Jane that he would send her a ticket if he found that he liked it there.

Keeping his word, he later wrote to Martha Jane. She wrote back, saying she would come. He sent the ticket. Aunt Mary, of course, protested, telling her that no decent girl would travel that far alone and unmarried. Martha Jane next enlisted the aid of her Aunt Ellen, a favorite aunt, who had a large family of children. Aunt Ellen told her and Aunt Mary that if Charlotte had married the man she loved, then Martha Jane could do the same. Martha Jane Harmer arrived in Chicago, Illinois on September 15, 1881. She was 23 years old.

James and Martha Jane had a long and happy marriage in the Chicago area, and had five children of their own. She lived to be 76 years old, passing away in 1934. Letters and photographs add leaves to the bare branches of a family tree and help us understand our ancestors as people and not just a series of names, dates, and locations. It’s never known where these gems will surface – in your basement, in the basement of a close relative, or somewhere entirely different, perhaps in the papers of a more distant relative you didn’t even know existed.

Wow! I would love to find a box like that, but I know that if it existed my mum would have already found it in her family history searches. You are very lucky to have such a treasure 🙂

Thank you for sharing the story, it was very interesting!

oh what a find! I have some old photos that I cannot place people and just wished that someone would have written something on the back! it can be so frustrating sometimes when dealing with all the unknowns.

Is this the same letter that has a story about a guy dying when his horses split going around a tree?

No – that was Charles Westerstrom, and the subject for a future post. You Deardorffs have a family tree full of interesting stories.