What would New England be without its mill towns? In what universe would mill towns like Lowell never have developed here?

Imagine an independent New England–a New England with its eyes to the sea and Boston its capital city on the coast. Perhaps its flag would fly an eastern white pine in its canton on a sea of red. The New England flag might even incorporate St. George’s Cross, a nod toward an independent New England’s close relationship with a Great Britain that powered its break from the rest of the United States during the War of 1812.

With its rocky soil and short growing season, an independent New England was never going to be a global powerhouse for agriculture … or cotton, which doesn’t grow much further north than southern Virginia. In the 1820s and 1830s, it would’ve been hard to build mill towns like Lowell with textile mills if cotton couldn’t be grown locally or bought at favorable rates from friendly states in the US south.

It’s in this vastly different New England that textile mill towns like Lowell may have never evolved. Our Massachusetts has more than forty-five mill towns–perhaps none more well-known than Lowell.

But, what would have had to happen for many of these mill towns to have never emerged? In what world would Francis Cabot Lowell’s Boston Manufacturing Company never have carved Lowell from East Chelmsford?

It could have happened–in a much different United States, the question is how?

1. New England would have seceded from the US during the 1814 Hartford Convention

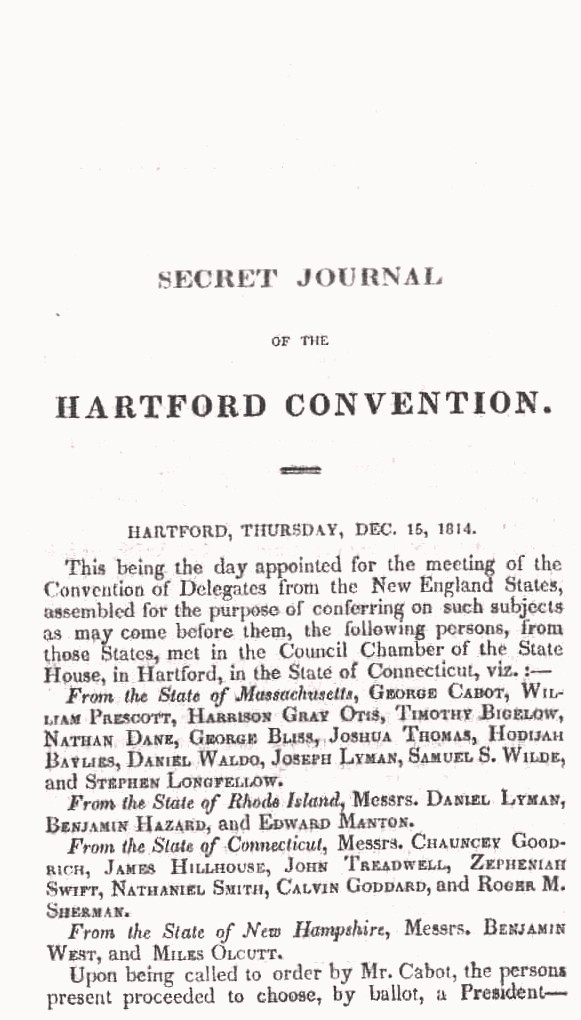

At the end of 1814, Massachusetts Governor Caleb Strong called for a convention that brought together the New England states to discuss everything that was wrong with America and which constitutional amendments might begin to help address these grievances. The delegates–all powerful New England men of their day–also discussed the idea of New England leaving the union.

The closed sessions of the Hartford Convention lasted three weeks into early 1815. They were so secretive that neither the proceedings nor the votes were recorded. Senator George Cabot of Massachusetts presided over the convention, but barely recorded any details beyond the formalities in his journal.

Twenty-six of New England’s most powerful men attended the Hartford Convention and discussed all the reasons New England was unhappy with the union. These included:

- Waning influence in the Electoral College – Through the Three-fifths compromise, New England felt unfairly underrepresented in presidential election vote counting

- Waning influence in the House and Senate – New states in the Midwest and South aligned with the Democratic-Republican party and not the Federalist party that was dominant in New England

- Waning alignment with national leaders – Presidents from southern states (Jefferson and Madison) had led the US into the War of 1812 and had put New England at greater risk of British attacks

The Hartford Convention very well could have led to a resolution calling for New England to secede from the United States.

2. New England would have arranged its own peace with Britain during the War of 1812

Separatist tension came to a head in late 1814, two years into the War of 1812 that had paralyzed the region’s ports and shut down New Englanders’ jobs and livelihoods. The British had invaded and were advancing through the Maine District of Massachusetts. They had attacked the White House. Many feared Boston would be next.

But, even surrounded by enemy British troops, the federal government still asked New England to send away its militia to defend other regions of the country. Every New England state except New Hampshire said no. President James Madison stopped paying the militia’s expenses and New England accused Madison of abandoning the region.

New England wanted an end to the war and not an end to their seafaring economy. They wanted the War of 1812 to end so much that Massachusetts Governor Strong sent a secret mission to discuss with Britain the terms of a separate peace to end the War of 1812 for New England.

3. Francis Cabot Lowell would never have left his first career

Francis Cabot Lowell never actually saw the city that would bear his name. Five years after he died of pneumonia in 1817 at age 42, Lowell’s business partners bought the site along the Merrimack River that would later become the cradle of America’s Industrial Revolution. But, Lowell almost never started his Boston Manufacturing Company in the first place.

Lowell was born to wealth and influence. John Lowell, his father, had been appointed to judgeships by Presidents John Adams and George Washington. His mother was a member of the prominent Cabot family of Salem, Massachusetts. Lowell graduated from Phillips Academy and later Harvard. By the time he was twenty, he set out for Europe to learn to be a merchant. In 1796, he became a merchant on Boston’s Long Wharf.

For the next twelve years, Lowell imported Chinese silks and tea and textiles from India. When his father died, Lowell used his inheritance to buy eight merchant ships. He joined other men and developed India Wharf in Boston for trade with Asia. He imported molasses from the Caribbean. For the first thirty-three of his forty-two years, Lowell invested all his energies into his seafaring import business–until the hostilities that led to the War of 1812 made shipping over sea a dangerous and uncertain business as Britain and France fought for control of Atlantic shipping routes.

Britain forbade American trade with France and her allies. Its Royal Navy seized American sailors and forced them to fight for England. France seized American merchant ships because the French had passed a law that said neutral parties could not trade with Great Britain. The US, some thirty years into its existence, realized it could not retaliate militarily. So, it passed its Embargo Act of 1807. Under the Embargo Act, American ships could no longer trade in foreign ports and cause more friction with Britain and France.

Lowell’s business, his fortune, and his entire future were at risk.

It was those hardships that drove Francis Cabot Lowell to conclude that the US should not be so dependent on overseas imports to sustain its economy. He set sail for Britain to learn how their textile mills worked, and then famously, memorized and brought that technology back to the US, to replicate it in New England under his Waltham-Lowell system.

Had the Hartford Convention called for New England independence and had the New England delegation reached peace with Britain in the 1810s, Lowell might have not embarked on creating his American textile empire at all. His prospects for continuing to source imports from overseas would have improved. And the promise of cheap cotton likely would have evaporated had New England’s relationship with the US South soured over an earlier war of secession, nearly fifty years before the US Civil War.

Lowell likely would have just gone on building his import empire.

4. New England independence would have ended, or slowed, its early 19c growth of textile mills

Francis Cabot Lowell’s textile mills weren’t the first in the United States. English immigrant Samuel Slater created the country’s first cotton mill in 1790 in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Although his “Rhode Island system” lacked Lowell’s later innovations that fueled the proliferation of the country’s mills, over sixty cotton mills already existed in the United States by 1810, primarily in Rhode Island and southeastern Pennsylvania. That’s the same year that Francis Cabot Lowell set off for Britain, frustrated by trade tensions that were eating into his import business.

By 1810, cotton represented more than 35% of all American exports and would have been even higher in a US without New England. Had New England seceded from the Union, with British help, the US South might have stopped fueling the rise of textile mills in New England. Instead, these mills might have arisen within the new, redrawn borders of the US–perhaps in the South (where the mills went after they left New England in the twentieth century). Meanwhile, the New England mill towns existing by 1810 would have had to source their cotton from somewhere else, or at higher costs. The business model would not have yielded the same profits and fueled the same growth.

New England independence would have fundamentally changed (or even ended) the growth of its textile mills.

Conclusion

New England never seceded from the Union, and never engineered its own peace with Britain during the War of 1812. In its aftermath, the war prompted a surge of interest in producing goods domestically within the US instead of importing them from abroad. A shrewd businessman, Francis Cabot Lowell, his associates, and other mill owners who followed him read the tea leaves and developed a domestic textile industry that changed the course of American history.

Without the American industrial revolution, New England would have been a far different place. Planned cities like Lowell and Lawrence in Massachusetts would have never been carved from earlier towns. New England the region, or would-be nation, would have continued trading with Britain, its largest trading partner, and kept developing its coastal and seafaring identity through commerce and a culture that reflected the products and people who arrived at her shores.

I’m very glad that Lowell existed because that’s where I got my first on-air job in radio at WLLH.