It’s not often that Lowell’s Civil War history gets its own real estate in the blogosphere. Lowell’s role in the Civil War often gets overlooked.

Nearly 160 years ago, Civil War General Benjamin Butler appears to have seized what’s now the site of the Lowell middle school that bears his name and built a training camp for recruits for the Massachusetts militia.

Few would disagree that Ben Butler was a fiery fellow.

When Ben Butler Created Camp Chase

Even before the war, Benjamin Butler was a well-known lawyer around Lowell. He made things happen.

He saw the sleepy, little plot of land out on Gorham Street past the Bleachery (later the site of the Prince Pasta plant). All that was in the way was the Lowell Fairgrounds, run by the Middlesex North Agricultural Society. Founded the year before, in 1860, the Fairgrounds promoted agriculture for people in Lowell and surrounding towns.

According to A. C. Varnum, the President of the Middlesex North Agricultural Society, Lowell never paid any money toward–or received any money for–Camp Chase when it suddenly appeared on the Lowell Fairgrounds in the months leading up to the Civil War. Butler just built a camp and the men came to join the militia.

The Fairgrounds offered an ideal spot for Butler’s camp:

- On Gorham Street, the Fairgrounds were a straight shot out of Downtown Lowell.

- Just a ten-minute walk from the Bleachery (later the Prince Pasta plant) on Moore Street, the Fairgrounds were only a half-mile from the train station there.

- Close to Lowell’s borders with Chelmsford and Tewksbury, men from the countryside could easily reach Butler’s camp at the Fairgrounds.

After the Civil War officially broke out in early 1861, Butler named his training camp Camp Wilson first and then Camp Chase, after Salmon P. Chase, then the US Secretary of the Treasury.

What Was Gorham Street’s Camp Chase Like?

(no images of Camp Chase appear to have survived)

Source

During the Civil War, several thousand men trained at the Gorham Street site. The 26th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was the first to arrive in September 1861, spending two months there before adding enough men and leaving in November. The 9th Connecticut, 12th Maine, and 30th Massachusetts all passed through that year. So did the Reed, Magee, and Durivage companies of the Massachusetts Calvary. In all, some 11 units trained at Camp Chase between 1861 and 1863.

Looking back years later, A.C. Varnum–that president of the agricultural society–told the Boston Daily Globe in 1895 that the recruits entertained themselves with “football, wrestling, jumping, and other athletic games and the playing of practical jokes” when they weren’t training.

General Butler ran a hard camp, it seems. “[The recruits],” Varnum continued, “got out of the guarded fairgrounds despite Gen. Butler’s orders to shoot them.”

“The recruits got out of the guarded fairgrounds despite Gen. Butler’s orders to shoot them.”

A. C. Varnum, 1895

Also in 1895, Maj. E. J. Noyes, who served in the calvary during the war, recalled that “the privates [at the camp] received $13 a month. The lieutenants received for pay, allowance for servants, and feed for horses about $120 a month.”

Noyes, who also ran a recruiting office in Lowell’s Appleton Block and a branch office on Lawrence’s Essex Street, continued, “The guardhouse was located about at the entrance of the camp. I looked into it one day, and thought it was a dark, ill-smelling place.”

How Did the City of Lowell Feel about the Camp?

With its textile mills, Lowell may have been more sympathetic to the South than many US cities and towns, given its reliance on cotton. However, when the Union’s 6th Massachusetts Regiment left Huntington Hall in 1861 and met a tragic fate in Baltimore that left Lowell residents Luther Ladd and Addison Whitney dead, support for the war grew.

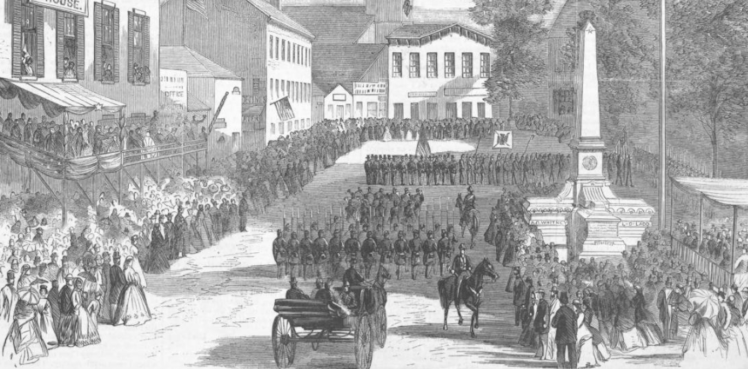

(Source Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 9)

And, presumably, that meant support grew for Camp Chase too. However, that didn’t stop local entrepreneurs from finding ways to earn a dime, or several, from the soldiers at the camp.

Recalls Noyes: “Medford rum was the drink those days. Near Davis’ corner [at the intersection of Gorham and Central Streets], a man was selling the stuff for eight cents a bottle. It was taken to the outside of the campgrounds and sold to soldiers for fifty cents a bottle.”

Noyes continued, “I have known instances where flavored water was passed into the men and there was some awful growling when the men came to drink the supposed rum.”

After Camp Chase

Thousands of men in at least 11 different units trained at Lowell’s Camp Chase before moving onto the battlefronts of the Civil War. After the Civil War ended in 1865, the Middlesex North Agricultural Society resumed using the land as an agricultural fairground for some 40 years until around 1905.

After the fairground ceased operations, the land became Lowell’s O’Donnell Park, which today also shares this site with the Shaughnessy Elementary School and the new Butler Middle School.